Fri, 01/31/2020 - 10:45

By: Kevin Kinback, MD Co-Editor, CTMSS Magnet Newsletter

By: Kevin Kinback, MD Co-Editor, CTMSS Magnet Newsletter

Article At A Glance:

- Background, pivotal trial data

- Device demographics, history

- Insurance coverage

- Protocol comparison OCD vs. MDD

- Tips and tricks for successful treatment

- OCD Bibliography

Background of OCD, pivotal trial, efficacy and outcome measures:

Patients with OCD suffer with obsessions, compulsions or both, with an annual prevalence rate of about 1.2%. Obsessions are repetitive, intrusive, and distressing thoughts, ideas, images, or urges often experienced as meaningless, inappropriate, and irrelevant. Obsessions usually persist despite efforts to suppress, resist, or ignore them, or use distraction techniques. Compulsions are repetitive, stereotyped behaviors and/or mental acts used to diminish the anxiety and distress associated with the obsessions. Obsessions and compulsions cause the patient distress and take up a significant amount of time. The clinical definition and diagnostic criteria of are specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and includes the degree of insight (good, fair, poor, absent, delusional) as well as the presence of tics.

The neurobiology of OCD has several models. One is the executive control model, where the deficits are defined as lack of impulse control and behavioral inhibition. Another is modulatory control, with deficits in regulating socially appropriate behaviors. The final model is the uncertainty disorder, which is an imbalance between input suppression and inhibition. Regardless of the model, imbalances in the cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical (CSTC) pathway are present. This pathway consists of multiple parallel interconnected loops between cortical and subcortical areas whose role is to determine which actions are selected as important and which are ignored. These regions include the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), cingulate cortex, caudate nucleus, striatum and thalamus. Abnormal functioning of this pathway results in impulsivity, compulsivity, obsessions, uncertainty, deficits in attentional allocation, sensory-motor gating, and modulation of motor activity, in addition to many other deficits.

OCD treatment with TMS delivers magnetic stimulation to the frontal brain structures and networks, targeting previously unreachable areas of the brain. The only FDA-cleared device is the Brainsway H7-coil, targeting the Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Positive results led to FDA-clearance in the Deep-TMS study, the only multicenter trial in OCD patients ever conducted. This study showed after six weeks of treatment, statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint results for the active treatment group when compared to sham (p=0.0127).

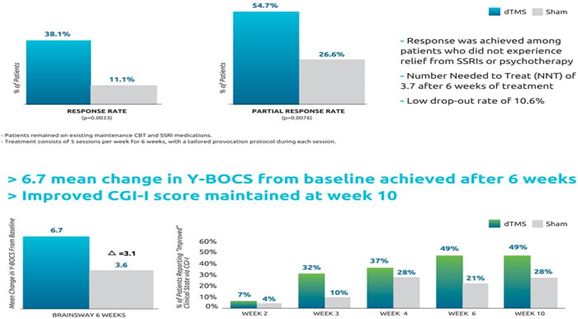

The improvement was maintained one month after the end of treatment at week 10. The primary outcome measure of this study was the OCD Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), the gold standard measure of OCD symptom severity. Importantly, 38.1% of patients in the active group achieved a response of more than 30% reduction in symptom severity as measured by Y-BOCS, compared with just 11.1% in the sham group (p=0.0033). Moreover, 54.8% of patients in the active group achieved a partial response of more than 20% reduction in symptom severity, versus just 26.7% in the sham group (p=0.0076). Data are summarized in the table below (courtesy of Brainsway USA):

OCD Pivotal Trial Summary:

Brainsway’s H7/HAC coil was specially designed to reach the anterior cingulate cortex, a key area of the neuroanatomical error detection system known to be altered in patients with OCD. After a successful pilot study of 41 patients identified the optimal stimulation parameters, a multicenter sham-controlled study of 100 patients with moderate to severe OCD was conducted. Patients were stimulated with either sham or active deep TMS after their individualized OCD-related symptoms were provoked. The most common adverse event was headache in both groups at a rate of 35%. The drop-out rate was 10% in both groups, primarily due to the intense schedule. The primary endpoint was the change in the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) score from baseline to week 6. The YBOCS is designed to assess the severity and type of symptoms in patients with OCD, the score decreased by 6.7 points in the dTMS group and 3.6 points in the sham group at the 6-week visit (p=0.0157). The improvement was clinically meaningful, which was evident by several measures such as a response rate of 38.10% in dTMS compared to 11.11% in sham. The NNT was 3.7. The efficacy of the Brainsway dTMS system, as measured by the YBOCS, never reached a plateau. Therefore, patients should continue to improve with more treatments over a longer period of time, especially if their baseline YBOCS was high. Additionally, patients and providers should expect improvements to be gradual. At week 10, four weeks after treatment, the benefits were sustained.

It is very important to note that the YBOCS scale is assymetrical in the question severity. This means that even a change of 1 point, depending on the specific question, can represent a major change in functioning. For example, the question about number of daily hours with active symptoms.

The HAC system was evaluated for OCD in a pilot single-center study followed by a multicenter clinical trial. The pilot study randomized 41 treatment resistant OCD subjects who were stabilized on their medications for eight weeks to one of three study arms. Fourteen subjects received sham treatment, sixteen subjects received high frequency (20Hz) dTMS treatment and eight subjects received low frequency (1Hz) dTMS treatment. The results of the interim analysis demonstrated that only 2 out of 8 patients in the low frequency group had decreased YBOCS. These results supported abandoning the low frequency arm of the study. Two subjects withdrew consent at the beginning of the study for personal reasons; and the remaining subjects completed the study in its entirety and without significant adverse events. The only reported adverse events were transient headaches, which resolved shortly after the treatment began. The high frequency group (20Hz) change in YBOCS was significantly different from sham. These promising results were the basis for the multicenter study.

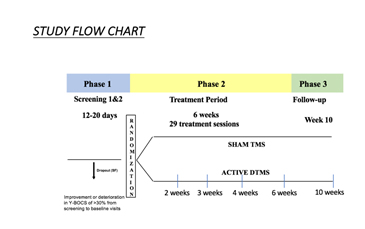

The multicenter trial recruited 100 outpatients from 11 sites, using the most effective parameters from the preliminary study (20Hz) in a prospective double blinded fashion. Subjects had all failed a previous treatment and were stabilized on their OCD medications for at least eight weeks. The study consisted of three phases: Screening phase (approximately 23- weeks, with no treatment); 6-week treatment period (daily treatment with dTMS or sham); and a follow-up visit 4 weeks after the study ended (the 10-week visit).

The primary endpoint was the change in the YBOCS score from baseline to week 6. The YBOCS score decreased by 6.7 points in the dTMS group and 3.6 points in the sham group at the 6-week visit (p=0.0157). The estimated slope in the dTMS group was -6.0 points across 6 weeks versus only -3.3 in the sham group. The difference between the slopes of 2.8 points over 6 weeks was found statistically significant (p=0.0127). The reduction in the YBOCS of 6.0 points is clinically meaningful and statistically significant when compared to sham. The effect size of 0.69 demonstrates a difference between the two groups, which is large enough and consistent enough to be clinically important.

Current state of OCD treatment, Number of devices and patients treated:

As of this writing there are at least 140 FDA-cleared H7 coils in use across the country to treat OCD. Brainsway is currently collecting data which is voluntarily shared by providers, but at this time the numbers aren't high enough to publish- but this is the goal. Data available at this time for 50 OCD patients who completed at least 29 treatments show that 32 met response criteria, correlating to a 64% overall response rate. These data are extremely encouraging. By the best estimate to date by extrapolation it seems that about 2,000 patients have been treated for OCD. Hopefully the publication of both the CTMSS guidelines for OCD (noted below) as well as the open label outcome data being collated by Brainsway, will go a long way to encourage payors to promptly adopt a reasonable coverage and payment policy for OCD.

Text of the CTMSS Proposed OCD Insurance Coverage Criteria & Treatment Protocol:

NOTE: This section, while finalized and proposed by the CTMSS Insurance Committee, has not yet received final approval by the Executive Committee and as such is provided here only for reference and should not yet be used in clinical applications.

There is no standard or uniform coverage policy for OCD to date. In fact, most payors still erroneously consider treatment of OCD with TMS to be investigational and experimental, when in fact, the FDA clearance is direct evidence to the contrary. The Insurance Committee of the Clinical TMS Society has formulated the following guidelines as a first step in forming a coverage policy:

Background: Deep rTMS (dTMS) with the H7 coil was cleared in August of 2018 as an adjunctive treatment for adults with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). In its approval, the FDA noted 38% of patients receiving dTMS had at least a 30% reduction in the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) score, compared with 11% of patients who received sham treatment(Carmi et al. 2019). Unlike Major Depressive Disorder, which tends to be an episodic illness, OCD is a chronic lifelong disorder typically beginning in adolescence(Pauls et al. 2014; Menchón et al. 2016). It is the fourth most common mental illness and can cause significant distress and disability. Obsessions, compulsions and avoidance symptoms, are correlated to abnormal activity in the cortico-striato-thalamic-cortical circuit (Ahmari and Dougherty 2015). Severe refractory cases are referred for neurosurgery (lesional or with an implanted deep brain stimulator)(Boes et al. 2018; Ooms et al. 2014; De Ridder et al. 2016; Neumaier et al. 2017).

Procedure & Protocol: A H-coil is placed over the anterior cingulate cortex, 4 cm anterior to the foot motor cortex and beneath the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex(Carmi et al. 2018; Carmi et al. 2019). The coil approved by the FDA in 2018 is called the H7 coil and is a type of deep TMS, or dTMS. dTMS for OCD is performed 5 days per week for 6 weeks for a total of 29 sessions. Prior to each treatment, patients undergo individually tailored provocations to activate the abnormal OCD circuitry (for instance, asking a person with germ-related obsessions and compulsions to touch the floor and then not use hand sanitizer). There is no need for anesthesia or analgesia, and there are no activity restrictions before or after treatment (e.g. driving, working, operating heavy machinery). NOTE: figure 8 coils are not currently FDA-cleared for the treatment of OCD.

Alternative treatments: Other non-invasive treatments for OCD include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy. CBT specific to OCD is known as exposure and response prevention (ERP), utilizing a trained cognitive behavioral therapist to guide the treatment(Foa and McLean 2016; McGuire et al. 2015). Pharmacotherapy options include serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline and fluvoxamine and the predominantly serotonergic tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine (Koran et al. 2007; Flament and Bisserbe 1997; Fineberg et al. 2007; Fineberg et al. 2015; Fineberg et al. 2013; Pittenger and Bloch 2014). These treatments typically have limited efficacy, and can introduce some control over, and reduction of OCD symptoms, but they do not usually result in remission.

Indications for Coverage: TMS for OCD should be prescribed by a licensed psychiatrist who is trained in the use of TMS, and if the patient meets the below criteria.

Criteria for Initial Treatment: TMS for OCD is considered medically necessary for use in an adult who meets #1 and #2 of the following criteria:

1. Has a confirmed diagnosis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) as per DSM-5 criteria

AND

2. One or more of the following:

Resistance to treatment as evidenced by persistent OCD symptoms after two indicated therapies (two medications or one medication plus psychotherapy) given at standard dosages, each for a minimum of eight weeks; CBT psychotherapy, while a treatment option, is not required as a pre-requisite to TMS OCD treatment; or

Inability to tolerate psychopharmacologic agents as evidenced by trials with two distinct psychopharmacologic agents; or

History of response to TMS for OCD in the past that was clinically meaningful; or

Resistance to treatment with CBT as evidenced by persistent OCD symptoms despite 8 weeks of ERP with a CBT therapist; or

If the patient is currently receiving antipsychotics, opioids, benzodiazepines, glutamatergic agents or other agents which could be considered investigational or relatively risky treatments, TMS may be considered reasonable and necessary and a safer alternative than additional treatment trials(Veale et al. 2014; Simpson et al. 2013; Rojas-Corrales et al. 2007); or

As an alternative to more risky and invasive treatments, such as Deep Brain Stimulation or psychosurgery, where TMS is less invasive and a safer alternative.

AND

3. The order for treatment: (or retreatment) is written by a psychiatrist (MD or DO) who has examined the patient, reviewed the record, and is prescribing or is collaborating with another clinician using an evidence-based OCD TMS protocol. The physician prescribing TMS shall oversee the treatment, but does not have to personally administer the sessions. This physician must be reachable and interruptible in case of problems.

Coverage Limitations:

The benefits of TMS use must be carefully considered against the risk of potential side effects in patients with any of the following:

Seizure disorder or medical conditions that may increase risk of seizure. There is always an extremely small chance for TMS to cause a seizure during the TMS session in non-epileptics(Lerner et al. 2019; Tendler et al. 2018). The seizure risk with TMS is small but more significant even in patients with known seizure risk factors(Pereira et al. 2016). There have been no reported seizures with the FDA approved H7 dTMS coil for OCD.

Repetitive TMS is contraindicated in the presence of an implanted magnetic-sensitive medical device located less than or equal to 10 cm from the TMS coil such as a cochlear implant. MRI safe and MRI-conditional aneurysm clips or coils, staples or stents are not a contraindication for TMS.

Dental amalgam fillings are not affected by the magnetic field and are acceptable for use with TMS.

Similarly, cervical fusion and fixation devices, hypoglossal and vagal nerve stimulators are not contraindications for TMS treatment.

Utilization Guidelines:

The treatment must be provided by use of a device approved by the FDA for the purpose of supplying deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. It is expected that the services would be performed as indicated by current medical literature and standards of practice.

TMS for adolescents with OCD may be appropriate if there is a higher level of treatment resistance. These cases should be reviewed individually for medical necessity and considered as a compassionate use.

TMS is reasonable and necessary for 29 visits over a 6 week period. Treatment extensions in 2-4 week increments should be approved based on clinical need with evidence of response from the first 29 sessions. Unlike treatment of Major Depression with TMS, treatment of OCD will likely require maintenance TMS, or at the very least a policy allowing retreatment of symptoms if there has been at least a 25-30% reduction in symptoms with a previous course of TMS therapy, lasting at least one month after the prior treatments ended. If patients cannot come in five days a week, treatments may be administered three days a week over a longer period of time.

CPT Codes for OCD TMS Treatment: there are currently no specific CPT codes for OCD, so the same codes as treating major depression should be used.

Differences between depression & OCD treatment with TMS:

- A different course of disease and treatment response: OCD is fundamentally different than Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Depression can either sometimes be chronic and continuous, and highly treatment-resistant in some cases, but can also have a relapsing/remitting course and have an episodic course. OCD, however, very rarely has spontaneous remissions. Even with the best psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies, treatment responses are modest, and a reduction of 30-50% from baseline OCD severity would be a very good response. In the OCD pivotal trial, a partial response was a 20% reduction, and a good response was a 30% response from baseline. However, nearly 80% of patients showed a measureable positive response, and at least some patients exceeded a 30% response rate.

- A different treatment coil: instead of a figure 8 coil, the deep TMS H7 coil is used, targeting deeper regions of the anterior cingulated cortex.

- Provocation is necessary: modest activation of the OCD brain circuits must be done just prior to starting OCD TMS treatment. This usually takes about 5 minutes and must be customized for each patient. The provocation does not need to be severe, but in some OCD patients, even mild provocation can be distressing to patients. Additional patient education is necessary to assure patient cooperation with the necessary provocation. If provocation is not used, the efficacy will be reduced.

- Different but simpler MT measurement: for the H7 coil used for OCD treatment, the MT is checked only along the midline starting at 8 cm from the nasion. Instead of the right hand, the MT is checked using the feet. Any toe, foot or ankle movement will qualify, and various positions within 1-2 cm anterior or posterior to the 8 cm mark can be compared for efficacy. The position showing movement in 50% of trains at the lowest power is the treatment location.

- MT vs. Treatment site: unlike MDD where the treatment site is 5.5-6 cm anterior to the MT location, the H7 coil is moved only 4 cm anteriorly for OCD treatment.

- Treatment power: Unlike MDD where treatment power is typically 120% of the measured MT, the OCD treatment is done only at 100% of MT. However, treatment should be started at much lower levels for shorter train lengths, and gradually increased per patient tolerance. The goal is to reach 100% MT over several treatments.

- Device settings: OCD device settings are 20 Hz, using 2 second trains at 20 second intervals, giving a total treatment time per session of 18 minutes.

- Outcome measurements: The primary outcome measure in clinical trials is the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (YBOCS). If depression is comorbid, other typical depression outcome measures can also be used. The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale can also be used.

- Total number of treatments: during the clinical trial, 29 treatments were used. However a higher number of treatments may be necessary to produce the best results. With outcome testing, it would be reasonable to start with 30 sessions (5 days/wk for 6 weeks), and then extend treatment in 1-2 week intervals as long as continued improvements are seen.

Tips and tricks for treating OCD successfully:

- Select OCD patients carefully: patients should be treatment-resistant, but stable. In the pivotal trial patients were treatment resistant and stable on either one FDA-approved medication or in maintenance psychotherapy. If a patient with OCD has never tried medications or psychotherapy, perhaps these should be tried before OCD is added. By nature of the clinical trial, TMS for OCD has been used as add-on and not monotherapy. If there are serious comorbidities such as personality disorders, uncontrolled anxiety or eating disorders or PTSD, or severe depression, it may make more sense to treat these first. Since depression IS covered by insurance for TMS treatment, severe comorbid depression could be treated first with an approved device, and thereafter, OCD treatment can be attempted. Always obtain written informed consent prior to TMS.

- Educate patients and set reasonable expectations: patients should be aware that similar to non-TMS treatments for OCD, complete remission is not typical. However the goal is always at least a 30% reduction from baseline. TMS treatment for OCD is likely best used in combination with pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy.

- TMS can hurt at first: be honest with patients about potential side effects, and start treatment at a much lower power than you think they can tolerate. Don't "spook" the patient by using high power right off the bat. The H7 coil seems "stronger," than the H1 (depresson) coil. Be sure to query patients about the level of discomfort of pain, perhaps on a scale of 1-10 and try to stay below 6-7. NOTE: Some patients may not be honest about the discomfort, so if they are displaying signs of pain, such a closing their eyes, tensing, or flinching, REDUCE the power. If patients feel they are subject to too much pain, they may discontinue treatment. Educate patients that tolerance to treatment site discomfort quickly develops over just a few days, so if they can "get over that hump," there will be much less discomfort going forward.

- Provocation can be distressing: for provocation, you need to customize it to the specific type of OCD. Most patients are able to describe what provokes them. This could be discussing their symptoms, thinking certain thoughts, or looking at images on a phone or portable device. A reasonable activation of the OCD circuits, perhaps to a level of 4-6/10 in relative severity, is sufficient. Educate patients that sometimes the OCD symptoms could temporarily worsen with the provocation. However coming to your TMS center daily, interacting with staff, receiving reassurance, and knowing that the odds of a positive response are good, will outweigh the distress associated with provocation. If you need assistance in setting up provocation protocols, contact the Brainsway trainers.

- Set expectations for maintenance and long term treatment: patients will need to have maintenance medication treatment following TMS, to prevent relapse or worsening. Additional courses of TMS, or maintenance TMS, may be necessary to sustain the treatment response. Doctors treating OCD with TMS are pioneers, and like TMS treatment for MDD, there is no specific proven or recommended protocol for taper, or maintenance treatment for OCD with TMS. Any maintenance treatment should be customized to patient response and should be tracked with outcome measures.

- Have additional help available: If not available at your own facility, develop a network of clinicians that can provide pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or CBT, or exposure & response prevention or ERP).

- Use the correct device: Figure 8 and other such coils have not been proven to reach brain structures involved in OCD, and should not be used in place of the HAC coil to treat OCD if insurance is being billed, since experimental devices are not covered. While off-label use of a coil cleared for another indication is not uncommon, most insurance coverage policies do not allow this for payment purposes. You should also check with your malpractice carrier, since devices lacking ANY FDA-cleared indication at all, are also usually excluded from coverage. This means if you are sued regarding OCD TMS treatment using a totally un-approved device, your malpractice will likely not pay for the defense or any judgment. An exception would be if you are running an IRB-approved clinical trial, which typically is covered by malpractice liability.

- Billing insurance for OCD TMS: prior authorization should always be sought. Some payors have issued authorization, but this is rare and on a case-by-case basis. Over time, coverage policies for OCD will be forthcoming, hopefully using the guidelines we suggested above, but for now, expect denials of OCD claims. However you should submit claims even without prior authorization. Denials should be appealed on levels 1 & 2 within insurance companies, and if not successful, using external appeal mechanisms, which usually involve Independent Review Organizations (IROs). Typically patients only have ONE external appeal available, so do not waste this trying for authorization, save it for appealing denials. Importantly, if you are a participating provider, you must have the patients sign an Advanced Beneficiary Notice (ABN) form. Beware: most payors including Medicare have their own specific forms which must be used, however a generic form may be acceptable. ABNs typically need to be signed on a day PRIOR to the first TMS in order to be valid, and patients must be given a copy. Additionally, your billed rates (charges) for OCD TMS should always be the same whether to patients directly or to insurance. Any discounts given to patients should be for documented cases of financial hardship. In this case, a Financial Hardship Agreement, in the form of a written document, should be used, signed by both the office representative and the patient, listing a specific cost per treatment, or a percentage discount, based on financial need. There should be a justification for providing a discount to a particular patient, as outlined in most insurance provider contracts. There is a clause in most insurance contracts known as "Favored Nation," which allows them to audit your charges and discounts. If they find that you are typically accepting payments from cash or insurance patients which are lower than the rates you are charging or accepting from insurance, the insurance has the right to REDUCE your payments to the rates you typically accept directly from patients. Note that this Favored Nation clause applies to payments for depression TMS treatment as well.

Summary: It has been well over a year since the FDA cleared the HAC deep TMS coil for treatment of OCD. There are neuroanatomical and other differences between MDD and OCC, including symptom pattern, chronicity, comorbities and responses to standard (non-TMS) treatments. It is important to understand the similarities and differences in protocols for treating MDD vs. OCD as well as the treatment responses. TMS treatment for OCD results in substantial improvements, but not typically a complete remission. Unlike MDD treatment, pre-OCD treatment provocation is required, a complexity for which additional provider and staff training is needed. Extensive knowledge, and clear communication with patients regarding the course of OCD as a disease, and TMS as a treatment is necessary to manage patient expectations and minimize barriers to treatment and other potential side effects and complications.

OCD Bibliography for TMS:

Blomstedt P, Sjöberg RL, Hansson M, Bodlund O, Hariz MI: Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. World Neurosurg 2013; 80:e245–e253.

Boes, A.D., Kelly, M.S., Trapp, N.T., Stern, A.P., Press, D.Z. and Pascual-Leone, A. 2018. Noninvasive brain stimulation: challenges and opportunities for a new clinical specialty. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 30(3), pp. 173–179.

Carmi, L., Alyagon, U., Barnea-Ygael, N., Zohar, J., Dar, R. and Zangen, A. 2018. Clinical and electrophysiological outcomes of deep TMS over the medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices in OCD patients. Brain Stimulation 11(1), pp. 158–165.

Carmi, L., Tendler, A., Bystritsky, A., et al. 2019. Efficacy and Safety of Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry, p. appiajp201918101180.

Fineberg NA, Reghunandanan S, Brown A, Pampaloni I: Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence based treatment and beyond. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2013; 47:121–141.

Fineberg, N.A., Pampaloni, I., Pallanti, S., Ipser, J. and Stein, D.J. 2007. Sustained response versus relapse: the pharmacotherapeutic goal for obsessive-compulsive disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 22(6), pp. 313–322.

Fineberg, N.A., Reghunandanan, S., Simpson, H.B., et al. 2015. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): Practical strategies for pharmacological and somatic treatment in adults. Psychiatry Research 227(1), pp. 114–125.

Flament, M.F. and Bisserbe, J.C. 1997. Pharmacologic treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: comparative studies. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58 Suppl 12, pp. 18–22.

Foa, E.B. and McLean, C.P. 2016. The Efficacy of Exposure Therapy for Anxiety-Related Disorders and Its Underlying Mechanisms: The Case of OCD and PTSD. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 12, pp. 1–28.

Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF: Comorbidity in hoarding disorder. Depress Anxiety 2011; 28:876–884.

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011.

Greenberg BD, et. Al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Mol Psychiatry 2010; 15:64–79.

Koran, L.M., Hanna, G.L., Hollander, E., Nestadt, G., Simpson, H.B. and American Psychiatric Association 2007. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry 164(7 Suppl), pp. 5–53.

Lerner, A.J., Wassermann, E.M. and Tamir, D.I. 2019. Seizures from Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation 2012-2016: Results of a survey of active laboratories and clinics. Clinical Neurophysiology.

Menchón, J.M., van Ameringen, M., Dell’Osso, B., et al. 2016. Standards of care for obsessive-compulsive disorder centres. International journal of psychiatry in clinical practice 20(3), pp. 204–208.

Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JAJ: Cognitive behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J Psychiatr Res 2013; 47:33–41.

Ooms, P., Mantione, M., Figee, M., Schuurman, P.R., van den Munckhof, P. and Denys, D. 2014. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorders: long-term analysis of quality of life. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 85(2), pp. 153–158.

Pereira, L.S., Müller, V.T., da Mota Gomes, M., Rotenberg, A. and Fregni, F. 2016. Safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with epilepsy: A systematic review. Epilepsy & Behavior 57(Pt A), pp. 167–176.

Pittenger, C. and Bloch, M.H. 2014. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 37(3), pp. 375–391.

Product Monograph, Brainsway deep OCD Treatment. Brainsway USA. 3 University Plaza Drive, Suite 503, Hackensack, NJ 07601.

Rotge JY, Guehl D, Dilharreguy B, Cuny E, Tignol J, Bioulac B, Allard M, Burbaud P, Aouizerate B: Provocation of obsessive compulsive symptoms: a quantitative voxel-based meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2008; 33:405–412.

Simpson HB, et.al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for augmenting pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry, 2008;165:621–630. (Reprinted in FOCUS 2010; 8:614–625).

Simpson, H.B., Foa, E.B., Liebowitz, M.R., et al. 2013. Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs risperidone for augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry 70(11), pp. 1190–1199.

Steketee G, Frost RO, Tolin DF, Rasmussen J, Brown TA: Waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for hoarding disorder. Depress Anxiety 2010; 27:476–484.

Tendler, A., Roth, Y. and Zangen, A. 2018. Rate of inadvertently induced seizures with deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Stimulation 11(6), pp. 1410–1414.

Veale, D., Miles, S., Smallcombe, N., Ghezai, H., Goldacre, B. and Hodsoll, J. 2014. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in SSRI treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 14, p. 317.

Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Lee CK, Newman SC, Oakley-Browne MA, Rubio-Stipec M, Wickramaratne PJ; Cross National Collaborative Group: The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(Suppl):5–10.